The Arg Presidential Palace in Kabul waives the flag of the IEA | Source: Tolo News

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

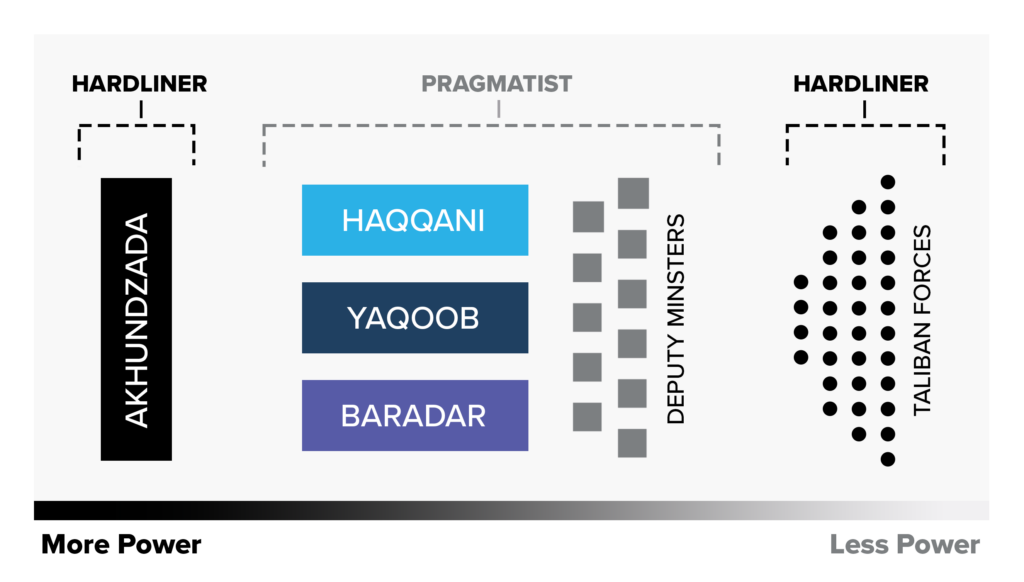

Internal Divisions: The Government of the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan (IEA) is split between hardliners and pragmatists. Hardliners are the IEA’s supreme leader and Taliban forces. Pragmatists include senior IEA leadership responsible for governance. This division, and the fragility of the IEA requires the pragmatists to ease the application of domestic reforms that are inline with international standards.

International recognition: The IEA has failed to get the international recognition it was initially keen on acquiring. It is assessed that the IEA has abandoned its quest for international recognition in favor of resolving internal divisions in the short term. The lack of official diplomatic recognition with foreign governments has limited the IEA’s ability to tap into Afghanistan’s foreign based assets.

Financing: Strict sanction regimes from western countries has hampered the IEA’s access to development aid and decreased foreign direct investment. China, and other neighboring states have begun investing into Afghanistan’s extractive and infrastructure sector.

Ethnic Divisions: The Taliban’s origins as an ethnically Pashtun and Sunni organization has alienated minority Tajik, Uzbek, Shia, and Hazara communities. The IEA has begun a process of homogenization of its government and military leadership to reduce infighting, marginalizing minority groups.

Resistance: Anti-Taliban resistance groups are mainly comprised of ethnic minorities and former Afghan government officials. These groups are most active in central and norther provinces. The IEA has a massive advantage in resources and manpower over resistance movements. Therefore, these groups do not pose a high risk to the IEA’s regime in the short term.

Terrorism: The threat of terrorism in Afghanistan remains high. IS-K has active cells in Kabul and along the border with Uzbekistan. IS-K targets civilians and IEA installations. The IEA cannot guarantee that terrorist factions operating in Afghanistan will not export their terrorism internationally.

THE TALIBAN’S AFGHANISTAN, ONE YEAR LATER

- August 15 marks the first year since the Taliban takeover. In its first year of governance the Taliban regime, or the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan (IEA), has encountered difficulty gaining legitimacy domestically. Frictions within the IEA have complicated it from gaining the international recognition required to develop its economy after twenty years of war.

- The IEA’s internal political differences reduce the government’s ability to provide resources to Afghanistan’s population which is geographically dispersed and fractured along ethnic, tribal, and political lines. Amid these complications, the risk of terrorism within, and from, Afghanistan remains high.

THE TALIBAN IN KABUL

A year in, the Taliban is split between rungs of its hierarchy that are either hardliners or pragmatists on issues of governance.

Hardliners: This wing is guided by the ideologically minded and militarily oriented members of the Taliban. Either component sits at opposites ends of the IEA’s power hierarchy. On the ideological side, Supreme Leader Hibatullah Akhundzada represents an ultra-orthodox interpretation of Islamic governance. The military component includes Taliban fighters, the foot soldiers that for 20 years fought against Western intervention in the country. Together, the ideological and military branches of the Taliban reject the notion that domestic policy be dictated by foreign demands.

Pragmatists: The senior IEA leadership that sits under Akhundzada is tasked with governance of Afghanistan and is more pragmatic. There are three main players in this camp, all of which are Akhundzada’s deputies; Minister of Interior Sirajuddin Haqqani, Minister of Defense Mullah Yaqoob, and Prime Minister Abdul Ghani Baradar. Each Minister contends with solving the myriad challenges in Afghanistan and accepts that solving these challenges requires negotiated solutions with relevant stakeholders. However, the IEA’s pragmatists are competitive. This is most evident in the armed clashes between forces loyal to Haqqani and Baradar.

HARDLINERS ON TOP

- As the government approaches its first year in office, it is assessed that the hardliners represent the more powerful of the two factions. The pragmatists understand that the IEA is still a fragile regime. Caught in between ideological leadership and hardline fighters, the pragmatists are careful to balance policies to ensure not to inflame either end of the power spectrum. Doing so risks ending their personal power, political careers, and worse, splintering Taliban forces.

- As a result of this political balancing act, the pragmatists have chosen to focus on appeasing Akhundzada and gradually reigning in the loose structure of Taliban forces. This has prevented the IEA from enacting reforms that the international community has set as a precondition for diplomatic recognition, namely inclusion of women and ethnic minorities. Implementing such reforms is too much of a risk for the pragmatists current grip on power.

- The pragmatists are not a homogenous group. The three ministers have deep differences as it relates to the pace of change in Afghanistan. Baradar is more progressive while Haqqani is more conservative. Additionally, issues of identity and allegiance to previous Taliban leadership complicate relationships between the pragmatists.

INTERNATIONAL RECOGNITION AND MONEY

- The IEA’s failure to get international recognition has complicated the regime’s post-conflict reconstruction. The lack of recognition, continued seizure of foreign assets, and strong sanction regime from western governments has terminated western financed development projects, hampered inflows of development aid, and decreased foreign direct investment. The lack of access to these foreign funds has created a liquidity problem for the IEA.

- Despite tight regulations on financing enterprises associated with the IEA, some development programs remain active in Afghanistan. These programs depend on special waivers offered by the US Treasury department. However, the inflow of development aid is a fraction of that during the war when 40 percent of Afghanistan’s GDP was provided by international aid. During the US/NATO intervention, foreign development aid by western partners and the UN, and its graft, was a vital source of income for Afghanistan’s economy.

- One of the few sources of foreign income provided to the IEA focuses on the country’s natural resources. Since the takeover, China has been quick to increase its investments into Afghanistan’s relatively untapped extractive sector. Aside from China’s investment, other neighboring countries namely Pakistan, India and Uzbekistan have sought to develop trade ties based on energy exports and transportation infrastructure. It is expected that China, and eventually Russia, will grow their economic footprint in the country.

IEA with China Ministry of Foreign affairs | Source: AsiaNews

ETHNIC DIVISIONS

- The IEA’s high level political challenges are compounded by locally rooted grievances that are based on ethnic divisions, religious extremism, and animosity from former government employees.

- The Taliban’s predominately religiously Sunni and ethnically Pashtun makeup has aggravated diverse communities in Afghanistan’s northern provinces, specifically in Shia Hazara and Tajik areas of the north. Weak command and control across Taliban forces and ethnic frictions has led to Taliban forces clashing between themselves over minor altercations.

- In light of these divisions, Taliban forces have begun the process of homogenizing the identity of their force structure, replacing ethnically diverse commanders with Pashtun leaders. While this ensures greater control over the Taliban as a fighting force, it exacerbates the country’s ethnic divisions and fuels the various resistance forces fighting against the Taliban.

RESISTANCE

- Since the takeover, resistance groups have spawned across Afghanistan in defiance of the IEA. These groups are predominately led by former government officials and members of the previous government’s Afghan National Security and Defense forces (ANSDF). The National Resistance Front of Afghanistan (NRFA) represents the strongest resistance movement in the country and is led by Ahmad Massoud. In May, Massoud launched an offensive against the IEA with coordination from other resistance movements in the country, the Afghanistan Freedom Front and the Afghanistan Islamic National & Liberation Movement. This fighting is largely concentrated in Central and Northern Afghanistan.

- The Taliban vastly outnumbers and outguns the resistance movements. Therefore, the resistance fighting represents more of nuisance for the IEA and does not present a significant risk to the existence of the IEA in the short term. However, the Taliban’s tactics in countering resistance forces does present a risk to the legitimacy of the IEA in the medium term. The Taliban have evicted, arrested, tortured, and executed individuals and communities suspected of collaborating with resistance groups. These tactics have inspired resentment withing communities in central and northern Afghanistan, fueling existing divisions within Afghanistan.

TERRORISM

- Terrorism remains a significant threat in Afghanistan. The Islamic State’s franchise in the Khorasan region, or IS-K, continues to launch attacks against Afghans and the IEA. Despite a major offensive against the organization in Jalalabad, IS-K retains a presence in Kabul and northern Afghanistan. The IEA has shown commitment to fighting IS-K and is keen on publicizing its tactical victories in arresting and killing militants.

- The IEA’s eagerness to publicize its counter terrorism activity is bias. The Taliban have not conducted operations against other terrorist organizations that represent a threat to foreign nations. This includes Al Qaeda (AQ), the Movement of the Taliban in Pakistan, Jamaat Ansarullah, and various groups hostile to India. The continued presence of these groups contravenes the Taliban’s assurances to foreign governments in which it promised to prevent terrorist organizations from using Afghanistan as a haven. The death of AQ leader Al-Zawahiri in Kabul indicates that the IEA is not actively purging against certain terrorist groups. This issue presents another obstacle in the IEA’s ability to secure international recognition.